Posted 7 years ago -

Did you know that today in 1888, a group of twenty young women from Malolos, Bulacan petitioned then-governor general Valeriano Wyler to open a “night school” under the tutelage of a Señor Teodoro Sandiko?

At the time, education was left entirely in the hands of the clergy which resulted in the lessons becoming too inundated with religious overtones. Although the students were taught simple arithmetic and reading the alphabet, education was not treated as integral as it is nowadays, and there was a wide disparity over the way boys were taught versus what girls were schooled. The generally accepted justification at the time was that women were destined to be homemakers and have no need for formal schooling beyond basic curriculums.

And so, only the daughters of the well to do were able to receive higher education at the time. Even then, virtually all of the secondary schools and colleges were exclusively for male students only during the Spanish Era.

Although a decree was issued in 1863 by Queen Isabella II that made primary education free and compulsory to all children in the country (including the teaching of Spanish to the populace), the endeavor ultimately failed. Although fingers were pointed towards a distinct lack of classrooms and instructors, the clergy of the time actively opposed the development. In their mind, it would be better to let the natives be ignorant of Spanish so that they can monopolize their position as among the few in the country who can speak both the native tongue and Spanish, thereby exerting control over the masses. In addition, they feared that learning Spanish would enable to natives to read books filled with liberal ideas, which was flourishing in the west at the time.

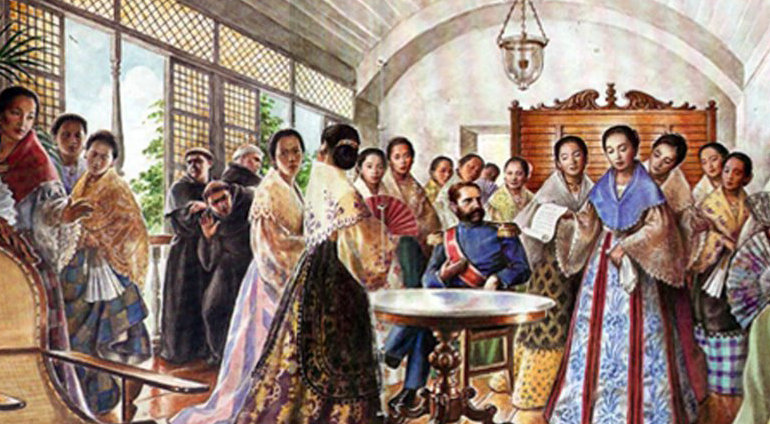

In an effort to change the status quo, the 20 women handed their letter to the governor general himself so that they can study the Spanish language and be more productive citizens, able to inform themselves and make decisions of their own accord.

Though the truth was that Sandiko, a professor of Latin and future senator of the First Republic, was already teaching them the Spanish language – albeit in secret. And so, he aided the women in drafting the letter in order to legitimize his classes.

As could be expected, the clergy vehemently opposed their proposition and convinced the governor general to deny it on the grounds that this “night school for women” would somehow pose a threat to the stability of the government.

Nevertheless, the women refused to back down and continued to petition Wyler – even going as far as travelling to Manila themselves in order to convince him to allow their request.

Despite the many setbacks that they encountered in their mission, the women ultimately succeeded. There were of course, certain stipulations: the women would finance their schooling, the teacher would have to be female (and not Sandiko), and that the classes have to be in the daytime.

Nevertheless, their success was a high point in Philippine history. Although the school was eventually closed down after only a couple of months, the women who were so instrumental in its establishment became active supporters of the revolution against Spain that erupted soon after.

So inspiring were their actions that even the national hero himself, Jose Rizal, wrote a lengthy letter praising their bravery and wisdom. He also commended their desire to be well educated, stating that education is the most fundamental source of liberation.

Loading Comment